Improving Completion Rates at Postsecondary Institutions is Critical for Student Success

March 01, 2017

By Peter J. Taylor, ECMC Foundation

Growing up with my education trailblazer father, going to college was never a question.

Born in the 1920s, he grew up in a time when civil rights were routinely denied to African American citizens and most colleges enrolled primarily white students. Given this, my father assumed that he would work on the railroads after graduation from high school.

When his vice principal asked him why he wasn't thinking about college, his response was: "Black boys don't go to college." Thanks to his vice principal's persistent support and encouragement, he bravely defied statistics and norms, enrolling at UCLA and later earning his Master's in Education from USC. In 1967, during an era of school integration controversies, he made history by becoming one of the first African American high school principals in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

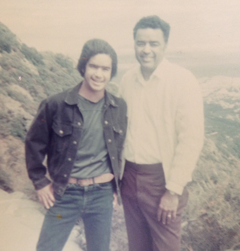

My father and I during my first year at UCLA (1976)

His legacy fuels my work in higher education and my belief that education is the key to overcoming poverty and finding success. It changed the trajectory of my father's life as well as the course of our family's future.

The challenges of college access that afflicted his generation are less prevalent today. While more students from underserved populations are able to access college in 2017 than in his generation, the goal of college completion has continued to be a hurdle.

There are too many people who start school and do not graduate. Only 46 percent of students graduate from public universities within six years. This issue disproportionately affects underserved students, which includes low-income students, students of color and first-generation college students. For example, 43 percent of white students graduate and attain their bachelor's degree within six years, compared to 21 percent and 16 percent among black and Hispanic students, respectively.

My father, James B. Taylor

The high cost of college tuition contributes to the problem and restructuring federal funding incentives for higher education institutions can help. When I was the CFO at the University of California, we spearheaded a proposal called Pell Plus. We argued that funding from Pell grants, a federal student assistance program for low-income students, should be given to institutions based on completion rates, not only enrollment rates; and that redirecting funding incentives could help push institutions to focus on approaches that help students persist and graduate. When students have financial assistance beyond their first year of college, they are more likely to complete. In addition, requiring postsecondary institutions to have "skin in the game" ensures a focus on completion.

Currently, both ECMC Foundation and Zenith Education Group* focus on improving college completion and retention rates for students from underserved populations. The College Success focus area of the Foundation invests the majority of its funding in programs that help students persist and graduate from college. We support innovative and evidence-based solutions that expand access to college and also help students to navigate institutional challenges in order to successfully graduate.

At Zenith, a nonprofit provider of career and vocational training, the team is leading a series of transformations on our campuses that are designed to improve student experience, increase completion rates and place more of our graduates in good jobs that pay family-sustaining wages. One of our first initiatives was to decrease tuition rates, making it more affordable for low-income students to attend, persist through our programs and graduate.

Every individual, no matter his or her background, deserves the chance to succeed. Through our work at ECMC Foundation and Zenith, we will continue to push for an education reform agenda that puts student success first.

Best,

Peter J. Taylor